The Tragic Life of Alan Turing

Hailed as the father of computer science, Alan Turing's life story could be one of the most complicated and heartbreaking you will ever hear of. Although he was a genius with an intellect beyond your dreams, he was also harbouring a dark secret – one that would eventually spell out his own demise. This is the tragic story of Alan Turing.

Early Life

Born on June 23rd, 1912, Alan Mathison Turing was born in a particularly tumultuous time in British history. He was born into a well-off family in London, as his father was a British civil servant in the Indian Civil Service. While this afforded the family a great deal of wealth, it also meant that both parents spent most of their time in India. When Alan was just nine months old, his parents returned to the other side of the world and left him and his older brother John in the care of some family friends. Now, I'm sure lots of you wouldn't mind some personal space from your parents, but at such a young age, this separation undoubtedly had a profound effect on the boys, with John believing that they had both been “sacrificed” to the British Empire.

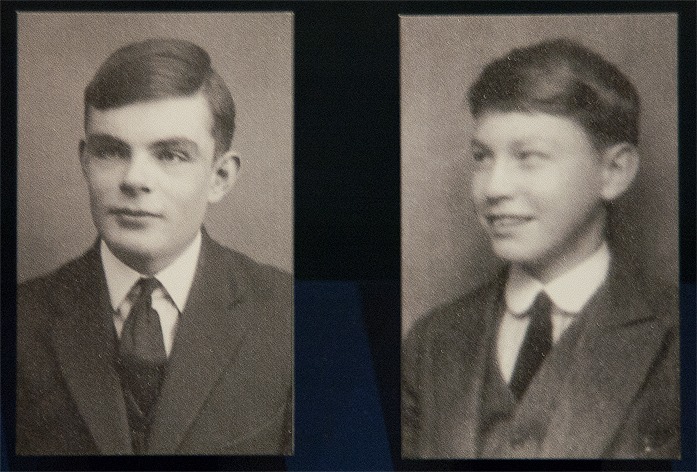

For the first eight years of Turing's life, he would bounce between foster care and his parents as they returned to England every few years. At the age of 10, Alan started at Hazelhurst Preparatory School, one of the best private schools that money could buy. Here, he learned to play chess and was regularly seen studying flowers on the hockey field rather than engaging in sports with his peers. When he was 13, he started boarding at Sherborne School in Dorset. This time of his life would prove to be one of the most transformative for young Turing, but also the most tragic.

Alan showed an almost obsessive interest in mathematics and science, which led to torment and isolation from his fellow classmates. He found it hard to fit in, as most boys his age were interested in girls and sports; neither of which interested him as much as numbers. His teachers became worried about him in other subjects, suggesting that he was not making the most out of his education. On a report card, his headmaster at the time noted, “If he is to stay at public school, he must aim to become educated. If he is solely to be a scientific specialist, he is wasting his time at public school.” It's crazy to think that one of Britain's greatest minds was underperforming at school. Gives some hope for the rest of us, right? That being said, Alan Turing did have an IQ of 185 and was considered to be in the top 0.1% in the UK for his high intelligence, so maybe it has a little more to do with that. Anyways, Alan's life was soon to change, in more ways than one.

Alan and Christopher

In 1928, Alan met Christopher Morcom, and the two formed a close friendship. Christopher made Alan realise that he wasn't some weirdo for liking science and maths, and they shared many heated conversations about their passionate study. This friendship changed Turing from the shy and isolated boy that he had become, into a driven and enthusiastic scholar. For the first time in his life, Alan began applying himself in class, and the change in him shocked his teachers who had all but given up on him. However, all was not as it seemed. Although everyone believed them to be close friends, Christopher was quickly becoming much more important to Alan than he could even comprehend himself. Although Alan was still young, he developed a fierce crush on his friend, wanting to constantly impress him with his intellect and dedication. Sadly for Alan, homosexuality was still criminalised in the 1920s, and gay men were regularly thrown in jail for being ‘indecent'. Knowing this, and expecting that his feelings would be unrequited, he keenly kept them to himself.

Tragically, this friendship and potential love story was cut short in 1930 when Christopher was suddenly taken ill and died at the age of 19. Alan was devastated and struggled to deal with the loss, unable to talk to anyone about his true feelings. He fell into despair and lost his sense of religion, focusing instead on where Morcom’s soul was and how he could see him again. He wrote to his mother, explaining his turmoil: “I feel sure that I shall meet Morcom again somewhere and that there will be some work for us to do together as I believed there was for us to do here. Now that I am left to do it alone, I must not let him down but put as much energy into it, if not as much interest, as if he were still here.” A tragic end to what could have been a beautiful love story.

University Life

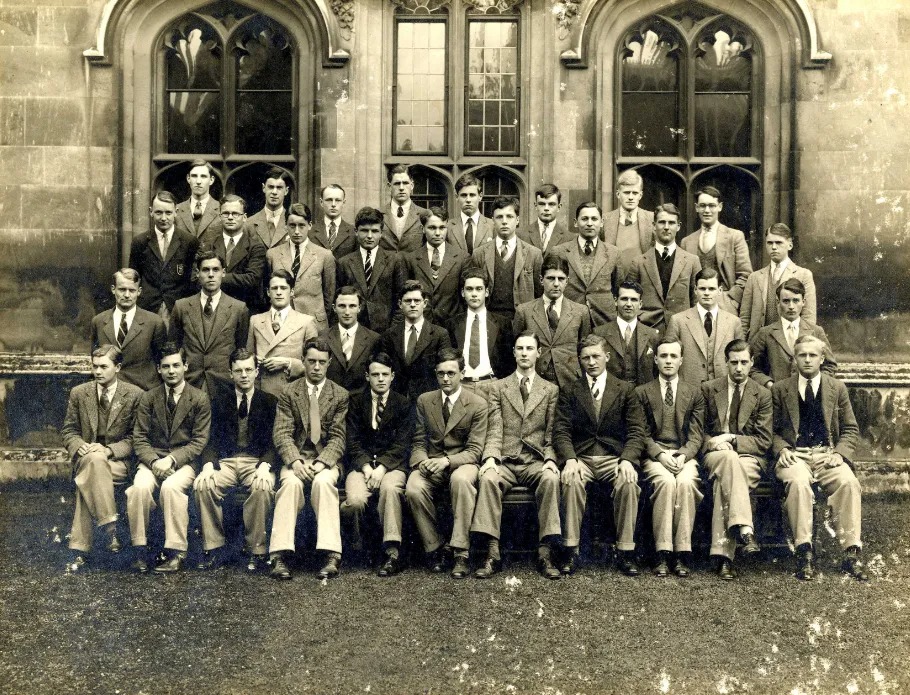

Alan Turing was accepted into Cambridge University in 1931 to study mathematics, where he truly began to excel and made a name for himself in his field. At the age of just 23, he was elected as a Fellow of King's College due to his impressive dissertation, which proved the central limit theorem, something that I cannot even begin to understand, let alone explain, but let's just say that it was very impressive. Soon after, he decided to pursue a doctorate in mathematical logic at Princeton University. While he was there, he published multiple papers, ones that again, I cannot for the life of me explain but this is where Turing started to explore cryptography, or ‘code-breaking', and would soon pave the way towards his most notable accomplishment – personally ending World War II.

World War II

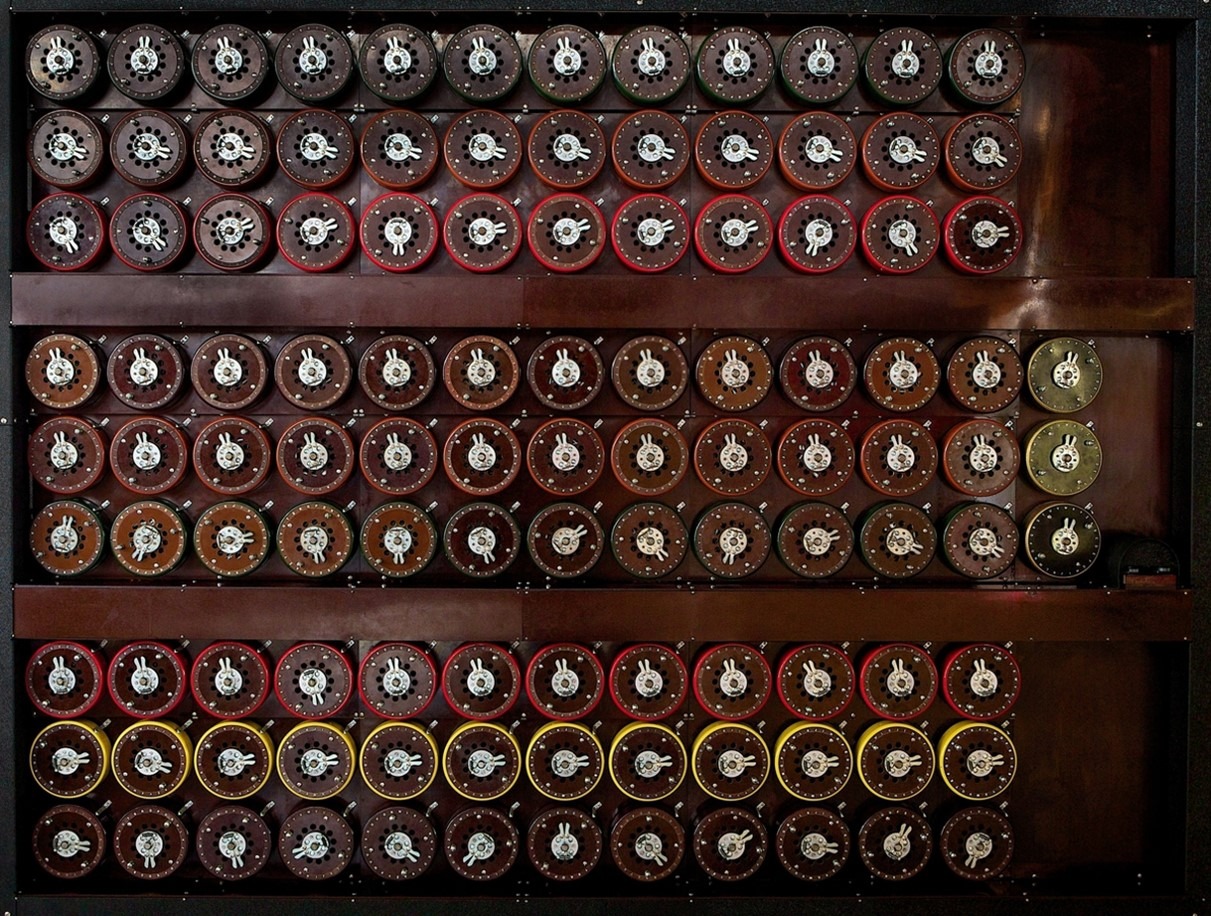

After graduating with his PhD in 1938, Turing travelled back to England and returned to his fellowship in Cambridge. As the threat of war began to loom over England, Alan started working part-time at the Government Codes and Cyphers School (otherwise known as GCCS). He was secretly recruited, along with other brilliant intellectuals, as the government prepared for a war that would soon wreak havoc across the world. These people were not just mathematicians like Turing, but had an amazing array of talents like linguistics, and chess prowess. Together, they were taught about the German Enigma machine, an incredible encryption tool that was impossible to crack. With 159 quintillion possible combinations and only 24 hours before the setting changed again, Britain knew that they needed their top scholars on the case if they had any hope of breaking such an impressive piece of technology. After months of baited breath, the news that the world was dreading was finally broadcast in September 1939: that Britain was at war with Germany. The stakes were now higher than ever, and so Turing was hired full-time and moved to Bletchley Park under strict instructions of secrecy. This is where the most important work of his life would begin.

Once the war began, Alan was hired into a team of nearly 10,000 people to work at Bletchley Park, all working day and night to decipher the seemingly random letters that the Enigma machine spurted out to them. It was frustratingly gruelling work – knowing that all their efforts of the day would become useless once the clock struck midnight. They were forced to throw all of their work away each day, slowly demotivating them each day as they failed to save their soldiers from Nazi attack. Despite the odds, these men knew what was at stake and what they would lose if they were to give up now. They worked tirelessly to crack the code until one day, Turing realised that they would need the help of something more advanced, something that the world had never seen before. When he told his colleagues, they thought he was mad and that he was wasting their time. Luckily, Turing knew better. After finally convincing his team to help him, they worked around the clock until finally, they did it.

They invented the Bombe in March 1940, a miraculous machine that could do the unthinkable: decipher Nazi messages and put an end to their reign of terror. This was a turning point for Britain, as they could finally see where and when the Nazis were planning their attacks. Over the coming years, the Bombe would uncover battle plans for numerous secret German missions and eventually be used to decrypt their defensive preparations for D-Day, where Britain finally brought the war to an end. It is believed that without this piece of equipment and the brilliant minds of everyone inside Hut 8, World War II could have continued for another 2-4 years, with no telling what the outcome of the war would be. It was truly remarkable.

You needed exceptional talent, you needed genius at Bletchley and Turing's was that genius.

Joan Clarke

Aside from his work, Alan had other interests although they were seemingly few and far between. While working at Bletchley Park, he met Joan Clarke, one of the only women working in her field. As a woman, her journey to becoming one of the top cryptanalysts in the country was very different from that of her male counterparts. She received a double first in mathematics at Cambridge but, as a woman, was not allowed to receive a full degree. When she was recruited to GCCS in 1940, she was initially assigned to clerical work in Hut 6, as a female cryptanalyst was unheard of. That being said, her employers couldn't ignore her talents for long, and she was eventually promoted to Hut 8 to work alongside Alan Turing at his request. She had met Alan briefly through her older brother at Cambridge, and the two became fast friends as they worked together to end the war. Turing always treated Joan equally to the rest of his colleagues, regardless of her gender as he was only interested in someone's intellect.

As time progressed, they began to spend more time together outside of work, coordinating their days off to go to the cinema or to take walks together. To Joan, their relationship seemed platonic, that is until in June 1941 when Turing changed the game. Knowing what we know of Turing's past, it would be impossible but Alan proposed to Joan, and she accepted. This would seem to be the end of it; the two would be married, have children, and grow old together. Unfortunately, Alan knew that this would never happen. Just a few days after he proposed, he revealed his ‘homosexual tendencies' to Joan, expecting this to be the end of their affair. Surprisingly, Joan was unbothered and continued the engagement, later stating in a 1992 BBC interview “Naturally, that worried me a bit, because I did know that was something which was almost certainly permanent, but we carried on." It's important to realise that nowadays we prioritise love and mutual desire but in the 40s, marriage was just seen as a necessity for women. Joan knew that Alan respected her intelligence and her work, which many men of the time would be intimidated by so it seemed like the match that would make logical sense to her. This arrangement worked for just a few weeks but the Alan's guilt grew too great. He knew that he would never be able to give Joan the love that she deserved and felt that he was robbing her of true happiness. With these fears looming over him, he quickly ended the engagement and set her free to find true love. They remained close friends up until Alan's untimely death.

Post-War Work

After World War II ended in 1945, Alan Turing and his colleagues went back to civilian life. As they had signed the Official Secrets Act when they began their work at GCCS, they weren't allowed to tell anyone about the work that they had done during the war, and so they received no recognition for the amazing work that they had all completed together. That being said, Alan moved to Hampton in London and began working at London's National Physical Laboratory, where he started creating the Automatic Computing Engine, the beginnings of the modern computer. He released many papers during his time working here and made amazing strides towards the creation of our modern world, thriving in his new environment. Aside from his work, Alan was also training to run in the 1948 Olympics, only missing out due to an injury at the last minute. Post-war life seemed to be going perfectly for him. Unfortunately, everything would soon change for poor Alan.

Arrest and Death

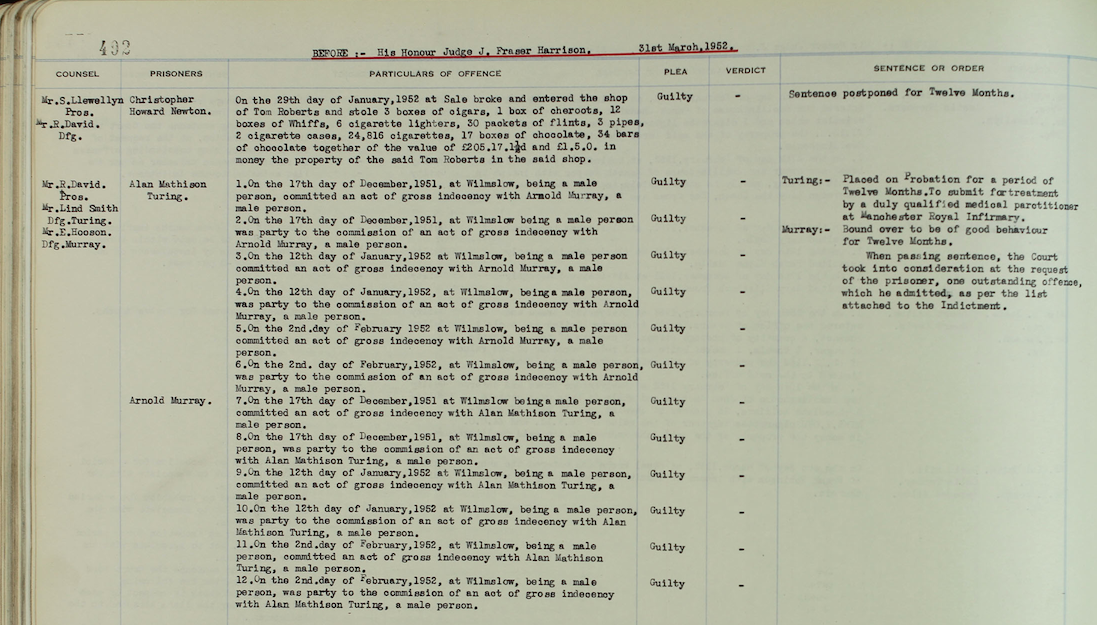

In December of 1951, Alan met a man who would permanently change the trajectory of his life. Arnold Murray was 19 years old at the time and unemployed when 39-year-old Alan Turing met him outside of a cinema in Manchester. The two seemed to get along well enough, and Alan quickly invited Arnold to lunch. The next week, the two spent the night together in Turing's home, where Arnold then robbed him of £8 (which would be the same as about £350 nowadays) and then swiftly organised someone to rob his house. What a nice guy, right? Now, Alan was pretty sure that it was Arnold that had organised the burglary but, despite everything, he still had feelings for him, so when he reported the crime to the police, he gave the wrong description to protect Arnold – something that would prove to be the beginning of his end. He was questioned over and over again until it became clear to the police that Alan Turing had sex with another man, something that was still illegal in 1951. They quickly ignored the burglary, and instead of treating Alan like the victim of a crime, they began their investigation to get him arrested instead.

Just two months later, Alan Turing was given the choice of two years in prison for gross indecency or two years undergoing chemical castration. He knew that if he went to prison, he would likely never work in his field again, so he opted for treatment. The conviction ruined his life, publicly shaming him for something he never wished to change and removing his security clearance for any intelligence or security jobs in the future. Still unwilling to give up on his life's work, he began oestrogen hormone therapy in March of 1952. As he started his treatment, he stated in a letter to a friend, “No doubt I shall emerge from it all a different man, but quite who I’ve not found out. Yours in distress.”

The treatment caused him to suffer greatly; he became impotent, grew breasts, and his depression deepened. Aside from his work, he had nothing left, and in the end, even that wasn't enough to sustain him as he sank deeper into the despair of hopelessness. Just a couple years after his conviction, Alan Turing took his own life on June 8th 1954, by eating an apple laced with cyanide.

Alan's Legacy

After years of dedication to saving his country, it was ultimately the same thing that let him down. Unappreciated and ridiculed in his time, save for the few that worked with him, it's disgusting to see just how Alan Turing was discarded by those he fought to save. After many secretive years, the truth of what Turing and his colleagues did for the war effort was released, and for the first time, Alan Turing was slowly recognised as the genius and war hero that he had been. In 2013, he received a posthumous royal pardon from Queen Elizabeth II for his conviction, something that could have saved his life just a few decades before. In 2019, he was voted as the most iconic figure of the 20th century by the British public, and in 2021, he was chosen as the new face of their £50 note. It is refreshing to see the life of Alan Turing finally being celebrated in the way that he deserved, but, as with many brilliant minds, the appreciation comes too late for the man himself, who died thinking that he was alone and hated.

Post a comment